For many around the world, ‘home’ and ‘workplace’ have become synonymous over the last year, with the COVID-19 pandemic driving a seismic shift toward working at home. As offices begin to reopen, workers will return — but Gensler’s ongoing workplace and residential research both show that many expect to work from home in some capacity moving forward. With this fundamental shift in how we live and work, developers, owners, real estate investors, and designers are asking: How can residential design evolve to support the growing at-home workforce?

We believe that residential design should accommodate the growing desire to work from home — at least part of the time. While we do not envision drastic measures, like movable walls and morphing furniture, design is a critical component in making homes more flexible, comfortable, and productive for remote work.

Our Residential Experience Index research draws a clear correlation between the design and experience of remote workers. The largest opportunity lies with multifamily housing, whose residents find their residences to be less conducive to working from home than their single-family counterparts.

The following insights explore varying design implications — all while reckoning with mounting pressures around delivery costs and affordability. Here are three key findings:

Key finding #1: Space is a prized amenity

For decades, a major trend in multifamily residential has been to reduce unit sizes to offset increased rents, leaving just enough space for a living room, a sleeping area, a tight kitchen, and perhaps a dining table. Today, one of these spaces is likely pulling double duty as a workspace.

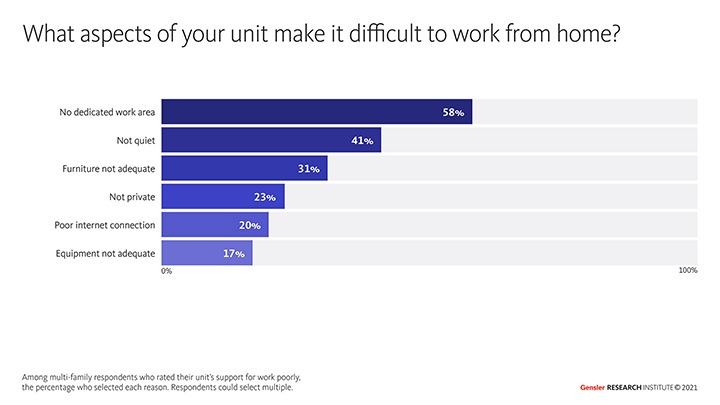

In contrast, lack of dedicated space was the most common complaint of survey respondents who felt their homes did not effectively support work. Inadequate furniture and equipment were also inhibitors to a successful work-from-home environment.

While average unit sizes are unlikely to increase any time soon, there are design opportunities that could address this issue at varying scales.

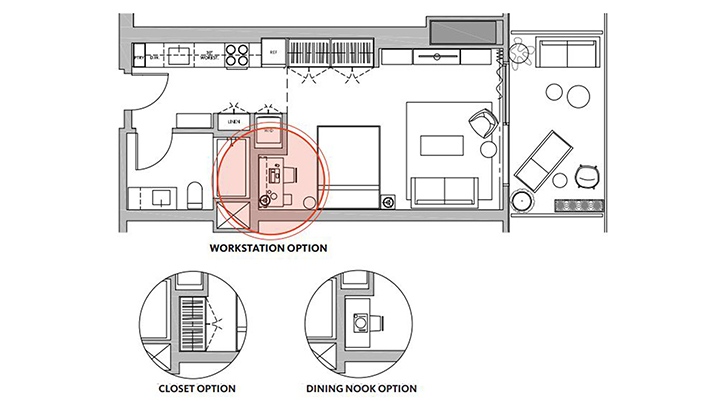

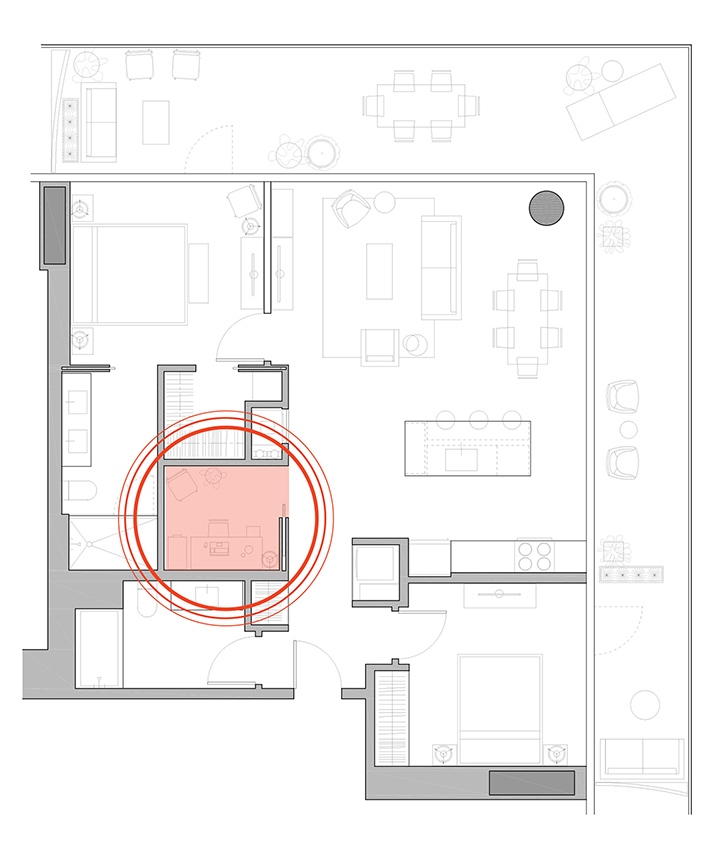

Design opportunity: the work nook

Dedicated workspace doesn’t necessarily mean a room with a door. Our research found that only 10% of multifamily survey respondents had access to a dedicated office space, but 73% felt their residence could still easily support work. This suggests that a small, well-designed workstation would have a positive impact on tenants working from home — even in the most compact units. For example, a well-placed nook in a studio could accommodate a series of pre-designed buildouts, including a work-from-home station. Other tenants might choose a dining table or additional closet storage, based on their preferences.

Design opportunity: the spare bedroom

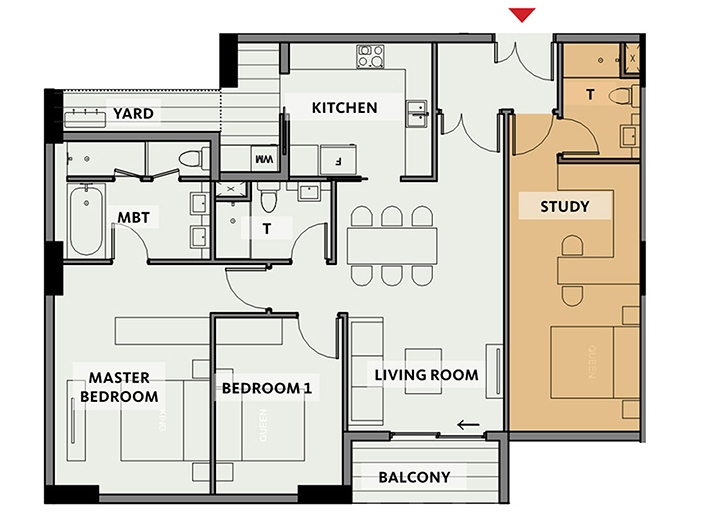

The unit mix within a residential building may be another area of impact based on these trends. We could see an increased future demand for two bedroom/one bath offerings, as residents seek units with an extra room to function as a dedicated home office.

Design opportunity: the lock-off unit

Another solution could be flexible “lock-off units” that come attached to a primary dwelling unit. Popular in places like Singapore, these secondary units are designed like a studio apartment and can function as a home office, an in-law unit, a mortgage-helper unit, or an extra bedroom when a family grows.

Key finding #2: Quiet, private spaces required to focus.

As we emerge from the pandemic, our workplace research suggests that most anticipate a hybrid work schedule — splitting their time between the office and home — but each workspace will serve a very different purpose. The office is viewed as the ideal venue for collaboration and social relationships, while the home is optimal for uninterrupted, focus work.

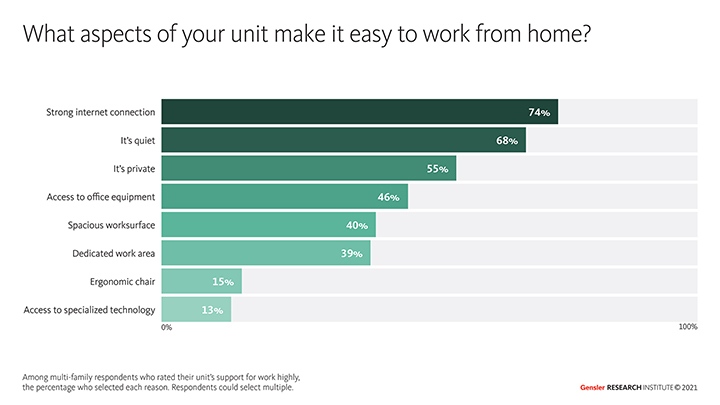

In fact, two of the top three most important features of an ideal work-from-home environment are quiet and privacy, according to our survey.

As such, residential workspaces need to support remote workers with a higher level of privacy and protection from distractions.

Design opportunity: soundproofing

One solution to ensure acoustic privacy is enhanced soundproofing — between and within units. This could include designing rental units to a condo spec for acoustic assemblies, such as double stud demising walls in lieu of staggered stud walls and improved exterior glazing assemblies.

Design opportunity: the den

A private, enclosed workspace is preferred by most to mitigate distractions. The addition of a den could be the size of a conventional bedroom or it could be a 50-square-foot space with a pocket door off the main living space. If designed properly, the latter could be implemented to a traditional unit layout without increasing the overall square footage. Either scenario would be an ideal place to maintain focus, visual separation, and acoustic privacy for tenants sharing a home with roommates or family.

Design opportunity: coworking amenities

While “business centers” have been included in multifamily residential projects for some time, they have evolved beyond a room with some tables and a seldom-used printer. It is reasonable to expect an increased demand for focus cabins and shared workspaces with varying degrees of privacy. While focus work is the primary concern for most, hosting in-person meetings and entertaining clients will still be a part of everyday life. Residential buildings will likely offer shared meeting spaces and small conference rooms to support this work as well.

Key finding #3: Connection to the outdoors and neighborhood support well-being.

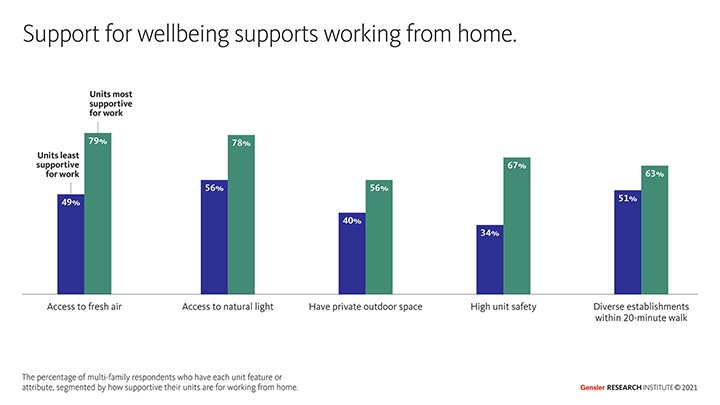

The pandemic magnified the inextricable link between the outdoors and our well-being. For that reason, it’s no surprise that our research found access to natural light, fresh air, ventilation, and a feeling of safety were all hallmarks of an ideal work-from-home environment. The survey also indicated that having diverse — but not crowded — establishments within a 20-minute walk had a positive impact on remote workers’ experience.

Design opportunity: bring the outdoors in

Over the last year, we have seen a dramatic uptick in clients requesting ample balconies and terraces for all units in their multifamily buildings. Not only do residents gain their own outdoor space, but they can blur the lines between indoors and outdoors with larger, fully operable doors and windows. Wind tunnel testing on our projects have shown that continuous balconies help slow exterior wind speeds and make outdoor living more comfortable.

Design opportunity: the 20-minute city

Without the need to commute, many residents working from home may elect to move away from city centers in search of a more affordable lifestyle. Because people still desire a walkable neighborhood, mixed-use principles of the 20-minute city (or 20-minute neighborhood) — where all a residents’ needs can be found within a 20-minute walk or bike ride — could satisfy cravings for the urban experience. This is true even in more suburban settings, provided we prioritize the pedestrian and micromobility to create spaces and experiences for people — not the car. This allows for more amenities, like dining, childcare, and green spaces to be located in close proximity to homes.

With a monumental shift in how we live and work, residential design is an area ripe for innovation. Designers and developers have the unique opportunity to shape multifamily experiences for this new normal, balancing the demands of an at-home workforce with the challenges surrounding affordability.

This blog is the first installment of Gensler’s Residential Experience Index — a deep investigation focused on the future of the home. Debuting later this month, this research points to shifts in how we think about the design of our homes and the resident experience.

Methods: This anonymous, panel-based survey of 9,000 residents was conducted online from January 20 to February 26, 2021. Respondents were required to live within the metropolitan areas of New York City, San Francisco, Atlanta, Austin, Dallas, Seattle, Chicago, London, or Singapore. Respondents were demographically diverse across gender, age, race/ethnicity, income, and education levels, and were residents of both multifamily and single-family homes.

Editor’s note: this article originally appeared on gensler.com