The Gensler Research Institute’s most recent Work From Home, City Pulse, and Global Workplace Surveys have revealed some surprising insights — and questions — about people’s perceptions about health and wellness and the future of the workplace. In this interview, we spoke with Michael Gao, M.D. of Haven Diagnostics and Assistant Professor (Courtesy) at Weill Cornell. Haven Diagnostics is a medical analytics company that helps employers quantify their infectious disease risk and plan a safe return to the office. Our conversation illuminated some truths in our research, debunked some common perceptions, and provided insights for the return to the office and the future workplace and design.

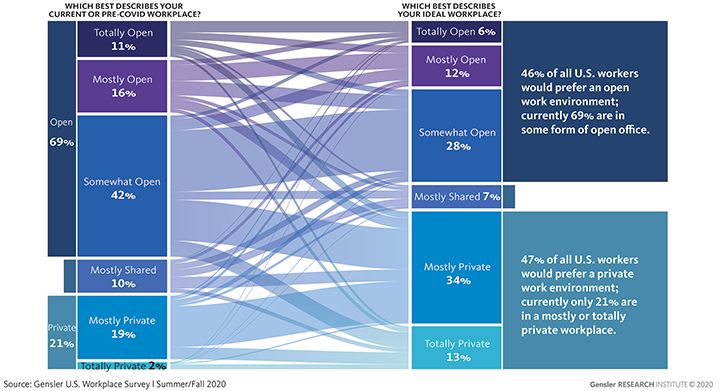

Janet Pogue McLaurin: In our U.S. Workplace Survey 2020, conducted this fall and summer, we measured current and ideal workspaces according to “degrees of openness” for the total work environment — taking into account not only an employee’s desk, but also enclosed conference rooms, team rooms, and huddle and focus rooms, which may be accessible for everyone to use. Most (69%) U.S. workers report they currently sit in a totally open, mostly open, or somewhat open workplace. Fewer people want to work in the office full time, and they want greater access to privacy when they come back. When asked about their ideal workspace, the results were split — 46% prefer an open environment and 47% prefer a private environment. We mapped the data reflecting the degree of openness that people had pre-pandemic or currently have to their ideal (see diagram below). It became readily apparent that the vast majority of respondents prefer a degree or two of increased privacy, but not a complete reversal.

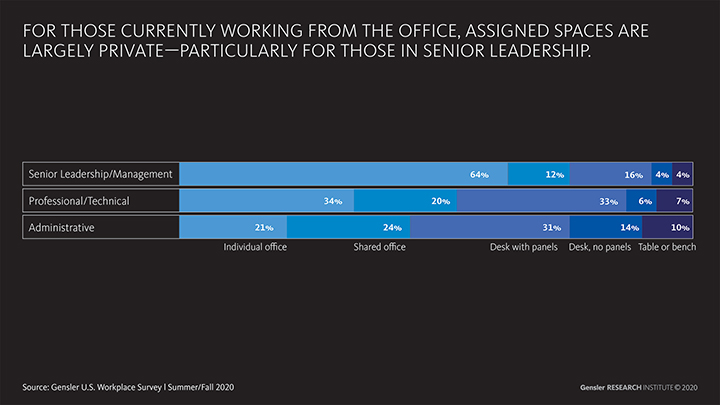

Christine Barber: Twenty-nine percent of the U.S. workers who participated in our survey report being back in the office full-time with 19% reporting they are “hybrid workers” who are coming back to the office on a part-time basis, working remotely the remainder of the week. For those currently working from the office, their individual workspaces are largely private (individual or shared offices), particularly for those in senior leadership roles.

We don’t know from our data whether these respondents have been assigned private spaces to work in post-COVID so they are comfortable coming back to the office, or if they are coming back to the hybrid workplace because they have the ability to choose private spaces to work in.

Is it necessary to have private offices to create a low-risk environment?

Dr. Michael Gao: The intuition that sitting in a private office is low-risk is a fair one: COVID-19 doesn’t go through walls, and almost no cases can be attributed to filtered air coming from ventilation systems (seen in modern offices) or to virus particles left on a desk surface several hours ago.

That said, private offices are not the only way to achieve a low-risk environment. Risk of transmission is related to whether employees with COVID-19 are in the office and the dose of exposure. The former can be modified by sick leave policies and vaccination rates, and the latter by policies around facemasks, distancing, time, number of people, and activity.

Many employees understand that good policies lower risk, but what’s counterintuitive is how dramatic the effect is: even with shared offices or open plans, our computational models show that in-office risk of transmission can be over 100 times lower than other common activities like dining in a restaurant. It is critical for office leadership to communicate this clearly.

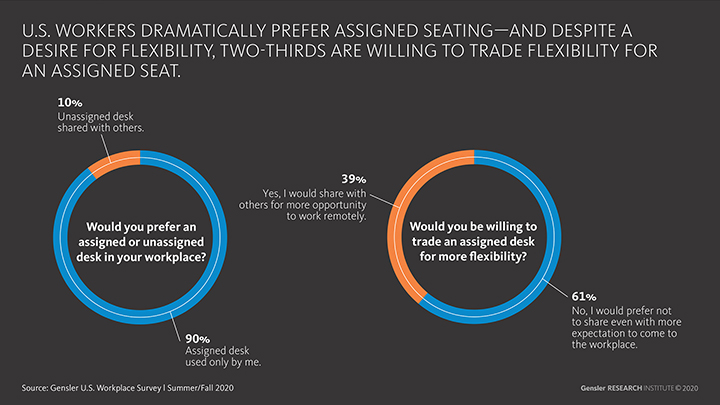

McLaurin/Barber: In Gensler’s most recent U.S. Workplace Survey 2020, we asked a really interesting trade-off question about desk sharing. We asked respondents if they prefer an assigned or unassigned desk shared with others. In the U.S., 90% prefer an assigned desk used only by them, which is much higher than we saw in the U.K., France, and Australia surveys we conducted at the same time. When asked if they would be willing to trade increased flexibility to work from home for an unassigned seat, most people (61%) said they’d still prefer not to share a desk, even if it meant coming into the office more frequently.

Most people in the U.S. say they prefer assigned seating. Is this just an irrational fear, or does sharing desks or offices really spread the virus?

Dr. Gao: In April and May, there was a lot of scary news about COVID-19 lasting on surfaces for days, but those early studies never found live virus — just genetic material (similar to what might be left behind at a crime scene where the perpetrator is long gone). To my knowledge, there still hasn’t been a single study that’s demonstrated transmission of COVID-19 through surface contamination several hours after virus was deposited. As a result, the CDC has updated their website to say that surface or object contact, especially for contact where someone was sitting the day before, is not thought to be the main way the virus spreads.

So while sharing a desk might feel uncomfortable, the idea that sharing desks results in COVID-19 transmission is not supported by current science. In fact, in the hospital setting in New York City, many of us used shared desks in staff offices even at the peak of the disease, and I do not know of a single case of COVID-19 that resulted from that.

When choosing between unassigned desks further apart or assigned desks close together, it makes sense to go with the former. We’ve seen offices where, although they were only at a quarter of their usual staff, all of them were from one business unit and sitting in their usual locations! That defeats the purpose of reducing staff levels in the first place.

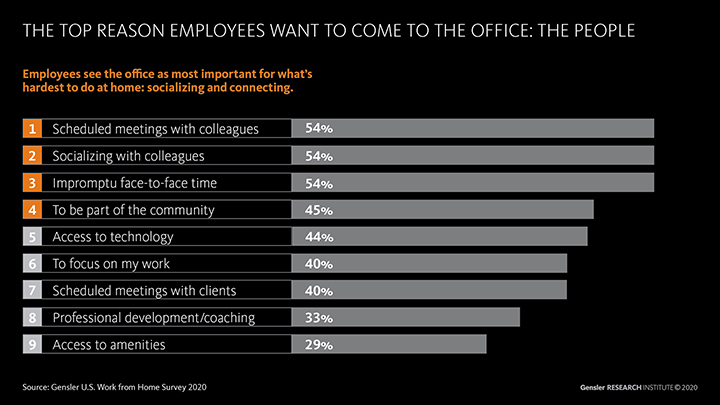

Barber: According to Gensler’s Work From Home (WFH) Survey, conducted during April/May 2020, the top factor people miss about the office is “the people.” Employees see the office as most important for what’s hardest to do at home: collaborating, socializing, and connecting.

McLaurin: We see these top reasons consistent in our most recent U.S. survey as well. It seems that the longer we are away from our colleagues, the more being together matters. Those whose jobs rely on working in-person with colleagues are especially missing the office. We miss interacting with each other; socializing with co-workers; being part of a community; and impromptu connections, which is often how mentoring and coaching naturally occurs.

Is the office really lower risk for face-to-face interaction, compared to other places where people may come together?

Dr. Gao: We all need social interaction. People interact in a variety of environments, including outside, at home, and in restaurants.

Outdoors is low risk because the large amount of air and the ventilation rapidly decreases the concentration of aerosols and droplets. But what few people realize is that the office setting, even in modern sealed buildings, typically has higher rates of outside air ventilation and better air filtration than the home setting.

In contrast, restaurants are higher risk not because of ventilation but because face masks cannot be used while eating, distancing is difficult, and the environment can be loud (resulting in speaking at a higher volume, which means more droplets and aerosols released). None of these factors are at play in the office setting: employers can provide face masks, space for distancing, and a quiet work environment.

What we see from the data is clear: a disproportionate amount of spread occurs in bars, restaurants, cafés, gyms, and weddings (even though people usually only attend a couple a year). Some have been traced to manufacturing and retail. But few outbreaks have been traced to the quiet office environment.

It’s clear that isolating at home for months is incredibly difficult, and we have a ways to go before a two-dose vaccine is fully administered to 200–300 million Americans. I think more thought needs to be given about how to help people socialize in lower-risk environments instead of higher-risk environments.

As case counts start to decrease and as vaccines start to be distributed, when can we return to a collaborative, creative, and social hybrid office environment?

Dr. Gao: We’ve seen multiple peaks and valleys thus far, but hopefully with the vaccines there are no more major peaks after this one. That said, it may take until Q4 2021 to fully achieve herd immunity.

In that context, employers who want to make the office available for staff will still need to take appropriate measures to reduce risk. Many employers think of these measures like a checklist, but this is imprecise — just as you might let your children play on a neighborhood cul-de-sac but not on a busy intersection, it does not make sense to apply the same rules to a Maine-based law firm with private offices and to a Montana-based call center in a dense, shared environment.

Instead, employers can titrate their safety measures based on their unique location and layout risk. On a week-to-week basis, levers that can be pulled include the number of people, the time they are spending in certain activities (e.g., meetings), and the level of enforcement. This allows for some degree of office collaboration, creativity, and socialization. As case rates fall and employees feel more comfortable, measures can be relaxed and productivity improved.

Editor’s note: this article originally appeared on gensler.com